Wait: SEVENTY years?

Yes, I know what you’re thinking. That would see the creation of the internet being in the early 1950s.

But this week marked the seventieth anniversary of our gracious Queen’s ascension to the throne. So I’m going to look at the past seventy years of technology that shaped the internet as we know it today.

The early days of computing

So, we’re starting in 1952, meaning that the pioneering work of Babbage, Lovelace, Turing et al. is behind us. It’s impossible to do justice to their incredible work – so I’ll just say that the people I mention next were standing on the shoulders of giants.

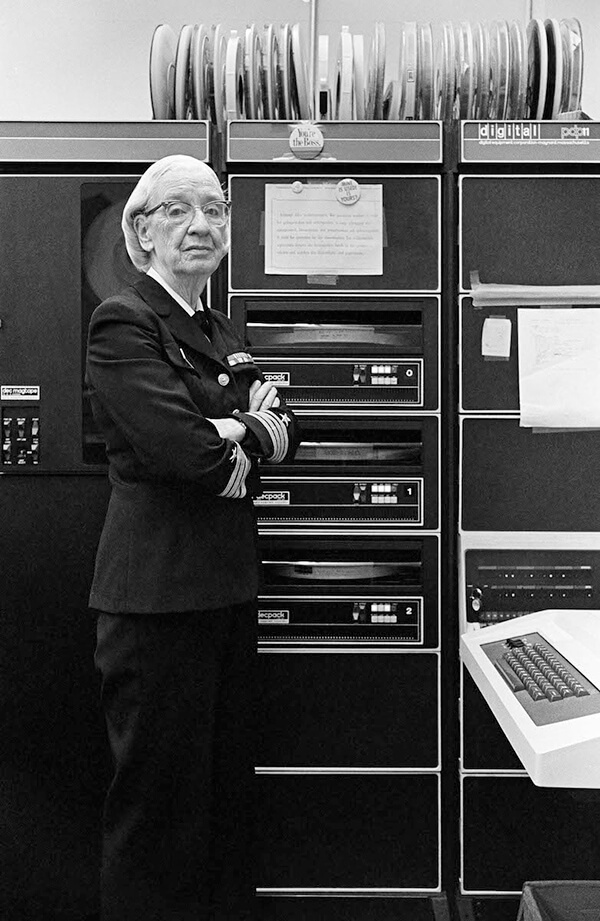

1952: Grace Hopper

You can’t have the internet without computer languages. Despite the vacuum tube nature of computers at this time, this was where the web started.

Grace Hopper was a key figure. It the same year that HRH succeeded the throne in 1952, Grace developed the first compiler: a way to write commands in English, which are then translated into machine code that a computer can understand.

As she said, “That was the beginning of COBOL, a computer language for data processors. I could say ‘Subtract income tax from pay’ instead of trying to write that in octal code or using all kinds of symbols.”

She was making computing less abstract and more accessible. Instead of it being confined to the realm of mathematicians like Turing, it helped start the democratisation of computing.

She wasn’t only a techie: she also became a rear admiral in the United States Navy!

COBOL and other ‘universal’ languages

Grace and her colleagues took part in the development of COBOL. She was the technical consultant to the committee at the 1959 conference where it was created. This business-focused computer language is still in use today.

Again, this helped democratise computing through its syntax, but it was also important in that it was designed to be used on different computers. In the 1950s, there weren’t many computers in the world compared to today, so standardisation was rare. Languages like FORTRAN and COBOL helped change that.

People could expect one input to achieve the same output, whatever computer was doing the calculation. They allowed for the possibility of millions of different computers talking to each other through the use of common languages.

Linking computers

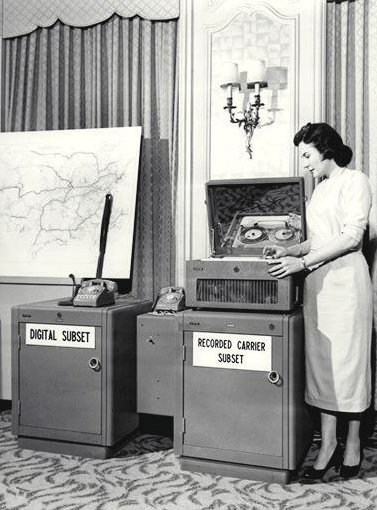

In 1958 Bell Labs released the first commercial version of the modem. Originally developed for radar systems, this allowed computers to pass information to each other using telephone wires.

The Bell 101 could transfer data at a blistering 110 bits/second. If that sounds fast, bear in mind that it would take 1455 minutes – over 24 hours – to transfer the 20i.com homepage!

It was also in the 1950s that people started to realise the potential of this networking, even if it was many years away. Inspired by library systems, people started to suggest the idea of cross-referencing information using a clickable ‘link’.

Ted Nelson gave it the name ‘hyperlink’, and the information it led to was called ‘hypertext’…

From valves to chips

The late 1950s onwards saw the forerunners of the microchip were developed at places like Texas Instruments, under Jack Kilby. In 1960, the first integrated circuit using silicon was demonstrated by Robert Noyce.

This would be revolutionary. It allowed computers to become smaller, cheaper and more complex. They were also more reliable: no need to replace all those valves!

Also, in the 60s, concepts like ‘personal computers’ began to crop up, even if it was only in science fiction. Star Trek is the most well-known example, with its ‘mobile phones’ and ‘iPads’.

Instead, people often ‘time-shared’ computers: they’d log in remotely, using telephone lines. This was common at educational institutions, like MIT and the University of Illinois.

Networks

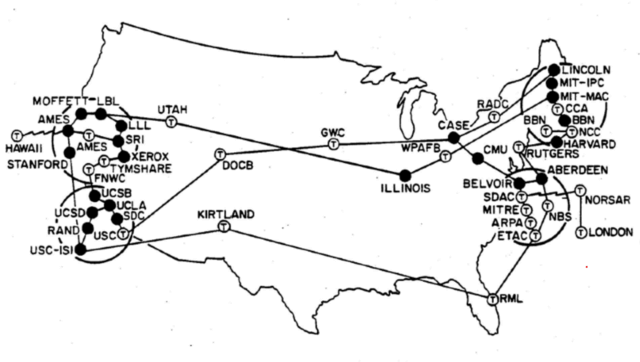

Computers, modems and telephone systems continued to improve in the 1960s, but it wasn’t until the 70s that we saw them properly networked. The first large-scale example of networked computers was ARPANET.

It’s reportedly a myth that the defence department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) primary goal was to create a command system that would be more likely to survive a nuclear attack. Instead it was focused on secure communication.

Nevertheless, a distributed network with no central ‘command and control’ would be resilient should the US come under attack. Grace Hopper was one of many who lobbied to develop ARPANET for military use in the 1970s.

Bob Kahn invented the concept known as ‘packet switching’. This meant that instead of messages being sent linearly (like talking on a phone), the information would be grouped into packets. Each of those packets would have a header identifying its contents, and many versions were sent across the network.

It meant that even if many packets were lost during transmission, the computer at the receiving end would be able to reassemble them into the full payload, such as a file.

Kahn was also key to the idea of ‘open architecture’, so that different networks running incompatible systems could talk to each other.

Other innovations from Kahn and his colleagues throughout the 70s would be the transmission-control protocol/Internet protocol (TCP/IP), File Transfer Protocol (FTP), and Telnet (remote login).

The first email

The first ‘killer-app’ on ARPANET was electronic mail. Raymond Tomlinson was the first person to create and send an email in 1971.

As he says in the video, he wasn’t sure whether it would take off, and made the email application in his spare time. The message to himself said “something like QWERTYUIOP” apparently…

Just after the Queen’s first jubilee, the first ‘spam’ email arrived in 1978. Against network rules, Gary Thuerk sent out the first mass email to approximately 400 people whom he thought might be interested in his digital equipment. He claims that it was really successful: email marketing was born.

Client-server relationship from 1974

It was clear that networked computers had potential, so futurologists had a heyday.

In this interview with Australian TV, Arthur C. Clarke makes one of his many predictions. He describes how ‘by 2001’, people might have something like a ‘console’ in their home (the browser) that networked with a far large computer elsewhere (the datacentre).

He got the whole ‘work from anywhere’ concept spot on, even if it took about twenty years longer to become adopted widely.

The first ‘web hosts’

While files were largely kept on the computers that were networked, there were still Interface Message Processors (IMPs). These were minicomputers used as nodes for packet-switching. They weren’t dissimilar to the switches used in data centres by web hosts today.

The first four IMPs were at the University of California (LA), Stanford Research Institute, the University of California Santa Barbara and the University of Utah. It shows that although the early net did have military applications, it was largely being developed in academia.

The ‘internet’ is named, and domains develop

By the early 80s, ARPANET had been divided into two parts: MILNET for the military and a civilian version still called ‘ARPANET’.

In 1983, the combination of the idea of communicating between these two networks and others was called ‘internetworking’. So the first ‘internet’ came about.

ARPANET was succeeded by many other networks. As the first PCs came out, and Local Area Networks (LANs) attached to the net proliferated, things became more complicated.

So instead of relying a single table where all the different sites on the net could be looked-up, the dynamic Domain Name System was developed by Paul Mockapetris. This distributed the list of IP addresses across many different locations, so there was no single point of failure.

This exists today as DNS. It’s why when you first buy a domain, it will take some time to propagate between systems around the world.

Plus, there was an issue with humans not being able to remember long lists of numbers, which form IP addresses. So instead, names had been used – and translated back in to the IP – since the 70s. However, it wasn’t until the mid-80s that a formal system of domain names were developed.

The first human-readable domain name was Nordu.net, created on 1st January 1985. However, the first domain was officially registered was symbolics.com. It remains live, as an internet museum.

That name you’ve been expecting

Tech continued to advance throughout the 80s, with computers and networking becoming more advanced, cheaper and widely available. The internet was thriving. But the World Wide Web was yet to come.

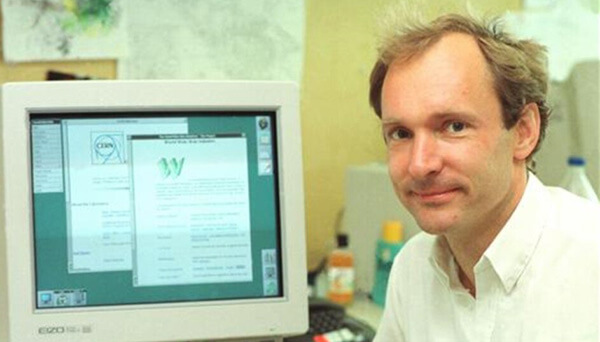

Tim Berners-Lee was working at CERN, home of the biggest particle accelerator, when he wrote ‘Information Management: A Proposal’.

While his proposal was described as ‘vague, but exciting’ by his boss, he was given time to work on it. By the end of 1990, Tim had created five things that would change the internet forever:

- The Uniform Resource Identifier (URI). The address of each thing on the web: text, images, files etc. A URL is a URI.

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). This allows resources (the ‘hypertext’ of the 50s) to be retrieved by a link.

- HyperText Markup Language (HTML). A way of presenting, modifying and formatting content on the web.

- WorldWideWeb.app. The first web page editor and browser.

- CERN httpd. The first web server.

Most importantly, he wanted the tech to be universally-available and decentralised. He made all the software free and open source. As he has said:

Had the technology been proprietary, and in my total control, it would probably not have taken off. You can’t propose that something be a universal space and at the same time keep control of it

Tim Berners-Lee

Tim remains an advocate of the open web and privacy today.

So while he didn’t invent the internet, he invented the World Wide Web. He made the possibility of having a website available to all. He created the internet as we know it: a place for websites.

Commercialisation

The internet really started to blossom in 1990s, thanks to Berners-Lee’s work. While there were 130 websites in 1993, there were 100K by the start of 1996.

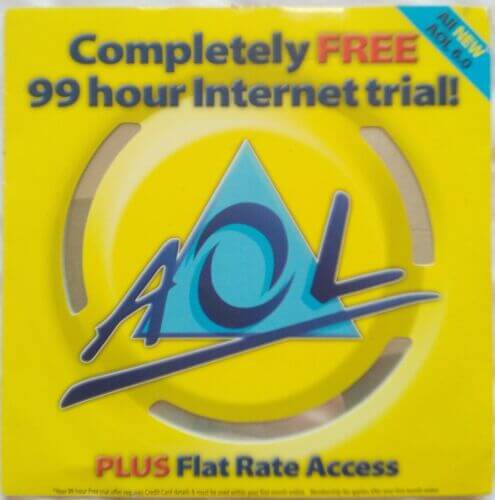

There were rivals to Berners-Lee’s open web: the ‘big three’ in the US were Compuserve, Prodigy and America OnLine (AOL). They served their own version of the web: curated, but effectively being ‘walled gardens’. They were highly successful from the late 80s to the mid-90s. But the open web was the victor in the end.

The early WWW was very ‘DIY’, mainly consisting of people’s personal sites. These sites – usually run by people working in tech but covering a range of subjects and opinions – were the origins of the ‘weblog’ (blog). People began to socialise using message boards (which became forums) and got social through messaging through Internet Relay Chat (IRC).

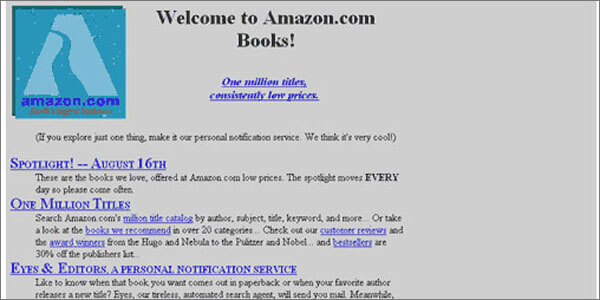

Some organisations and academia had their own sites, but it was very limited. It wasn’t until 1994 that websites themselves started to become more commercialised. It was the year that Amazon and eBay started, and Pizza Hut started their first delivery portal.

1995: Hackers

As we know, the movie Hackers is the highpoint in the history of human technology and culture. It’s the reason why all web developers are so proficient on roller blades.

It remains the most realistic portrayal of cyberspace ever created, and as such, it was a turning point in the popularity of the web. It made the web cool: hack the planet!

OK – I’m not being entirely serious there, but my point is that interest in the internet was growing so much that popular culture responded. The web had gone worldwide.

The browser wars

It appeared that there was money to be made, so big business started to move in. But how would they get a foothold? The web was effectively ‘free’ and uncontrollable. What they could control is the way you accessed the web.

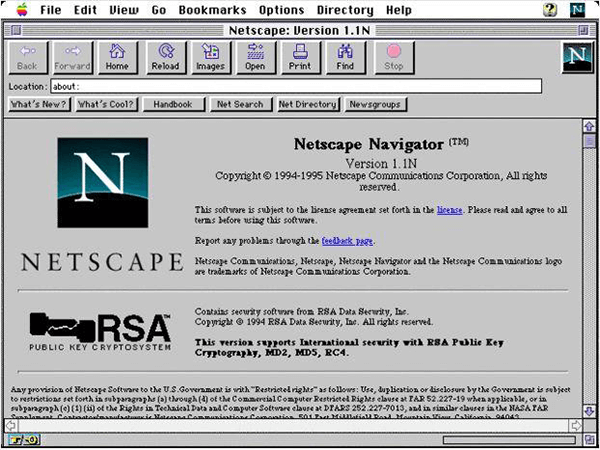

Early browsers like Mozaic had been defeated by Netscape Navigator, which became the dominant way to browse the web.

In 1995 Microsoft offered to buy them out, but they escaped to carry on and release version 2.0. Brendan Eich from Netscape was able to add new technologies to this version, like Javascript and CSS. It made websites a whole lot more functional, easier to code and prettier to look at.

Microsoft didn’t give up, though. Through having the advantage of being able to package their browser (Internet Explorer) free with Windows, they gained ground. Eventually, IE was the winner of that browser war.

That wasn’t the end of the Browser Wars, though. Eich moved on to Mozilla, the birthplace of Firefox, and he continued to innovate there.

Even more recently (long after other similar wars, like the Great Chrome Invasion), he introduced the privacy-focused browser, Brave, in 2015.

What will happen to that remains to be seen, but we wish him luck.

The origins of 20i

In 1997, brothers Jonathan and Tim Brealey entered the internet business in the form of Webfusion. Their aim was to simplify the process of getting a website online, and they were extremely successful, becoming the largest UK web host.

They also pioneered Reseller Hosting. They were the first to offer accounts where ‘web designers, entrepreneurs and internet consultants’ could re-sell web space to others.

Jonathan and Tim went on to found 123-reg, which helped getting a domain name a lot easier – and cheaper!

Later, they were to form Heart Internet, and in 2015 they started the journey that would become 20i as it is today.

Finding stuff on the web

As the web expanded, it became more and more difficult to find information. There were links from sites and blogs, you could type things in from leaflets and magazines, but if you wanted to find something new…it wasn’t easy. A central list of websites was updated manually up to 1993, but in the explosion of new sites, this wasn’t possible.

The first directory of the web that we would recognise as a search engine was Archie from 1990. However, this was literally just a file search – it couldn’t index the file contents. So for example, if you searched for ‘home’, it might have shown you a list of every file called ‘home’ – not so helpful.

The first search engines were more like directories, but the most popular one in the mid 90s – Yahoo! – introduced a search bar in 1994.

In 1996, the first patent for ranking pages by the number of links that lead to them was registered by Robert Li, who went on to form Baidu. In 1998 Google’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin patented PageRank, which was similar.

By ranking search results based on trustworthy, authoritative links, they were able to out-perform other search engines. This, combined with a clean, simple design, meant that Google rose to dominate search during the latter part of the 90s. The rest is history.

The dot-com bubble

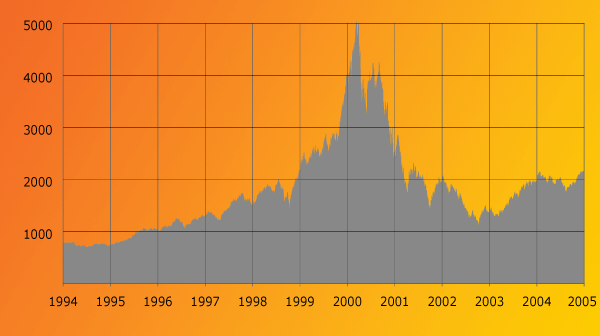

Whenever a revolutionary piece of technology arrives, investors tend to ignore it for too long (‘it’s just a flash in the pan’), then vastly overcompensate (‘I don’t care about what they do, get me TrashBat.com at any price!’).

From 1995 until 2000, investors were in that over-compensatory mode and the ‘dot com’ boom began. People were willing to pay a lot for startups that weren’t much more than a domain name and a good idea. Lots of money was lost around the turn of the century as those ideas fizzled-out and companies went bust.

However, for those web companies that survived the turbulent early 2000s – Amazon, eBay, Google, PayPal and so on – the dot com bubble was a blessing. As there’d been so much investment into the infrastructure of the web during the bubble, it meant that it was it was (relatively) cheap for these survivors to expand and consolidate. And consolidate they did.

Web 2.0 and social media

Up to the early 2000s, if you wanted to make changes to something online, in most cases you’d have to code those changes. Web 2.0 offered the opportunity for non-coders to update content on a web page ‘live’, and for those changes to be seen instantly by others.

Through the use of Ajax and JavaScript frameworks, the web was about to become a lot more interactive and dynamic.

Places like Wikipedia were founded, where anyone could help curate the world’s knowledge. Collaboration tools like the Google Suite allowed people to work on documents simultaneously. Forums, blogs and media sharing sites like YouTube proliferated.

We could get maps and directions to anywhere in the world. Through tech like Street View, we could visit anywhere on the planet.

But the biggest Web 2.0 change – even if it seemed relatively innocuous at the time – was the arrival of social media. MySpace was probably the first globally-successful network, but its achievements were overshadowed by Facebook. Since then, there have been many imitators/challengers to the social media space – but Facebook and Twitter have been the most long-lasting networks so far.

Social media’s influence on society has been huge, from helping create governments (and bring them down) to changes to individual psychology, behaviours and relationships. Its effects – both good and bad – is something for future historians to argue over.

A world in your pocket

Tied to the popularity of social media, demand for an always-online lifestyle soared. Laptops were fine, but still cumbersome: we wanted the internet in our pockets.

Mobile phones and text messaging had been around for many years. There were ‘smart phones’ and PDAs with internet connectivity. But it took Apple’s innovation, design and marketing skills to finally offer the answer in 2007: the iPhone.

The iPhone was revolutionary, but not just in itself. Their imitators were also influential: cheap Android phones brought the internet to a whole new audience worldwide.

It wasn’t just that these smartphones included web browsers. Apps would now also be internet-connected, and they’d help with global adoption by paying to be included by default on phones.

It led to mega-corps like Google and Facebook helping to bring the internet to developing countries.

So for many, a phone is their first and only way to access the internet. As such, in recent years web design has had to take in to account phone performance and responsiveness: ‘mobile first‘.

Running out of addresses

IPv4 was introduced 1983. At the time, having IP addresses made up from 32 bits seemed like way more than enough. It was enough for 4.3 billion internet addresses – we’d never run out, would we?

But yes: we are running out. So, since the early 2000s IPv6 has been gradually adopted. It uses 128-bit addresses: enough for 340 trillion, trillion, trillion unique addresses.

That’s a difficult number for a mere human to imagine, so here’s a way of thinking about it. Imagine that the surface of the earth was the IPv6 address range. You could divide the whole surface into square centimetre chunks, and each chunk could be given an entire IPv4 address range. And there would still be some left over at the end…

So IPv6 should be enough – let’s hope so!

Broadband shrinks the world

Network performance has improved exponentially since the time of our Queen’s early reign: not 101 bits per second, more like 100 million bytes per second! Having a broadband account of that speed or more is the norm in most Western countries.

Fibre optics – invented in the 60s, but not deployed at scale until the 80s – have meant that information can be transferred reliably at the speed of light. Ever-improving hardware has meant faster switching equipment, and more bandwidth for all.

As bandwidth increases, the internet seems to expand to fill it.

Most recently, media streaming has become the #1 source of internet traffic, while traditional broadcast TV and cinema have struggled to keep pace with the likes of Netflix.

Online shopping and communication

Since 2010, websites and the tech they’re based on has improved drastically. It’s meant that online shopping has grown exponentially in the intervening years, and we’ve grown to rely on it.

This was most apparent during the 2020-2021 pandemic. It’s hard to imagine how well we would have coped without the internet to help track outbreaks.

The pandemic highlighted our internet dependence in other ways. Without social media, video chat and streaming media, people would have had a harder time.

Of course, there’s a downside to our reliance on the internet. It’s still a fragile technology that could be disabled: by a large solar storm, for example. Online shopping has damaged our high streets and shopping malls, changing the architecture of our cities.

Then there’s bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, which wouldn’t have been possible without the internet. Finance had already been affected by near-instant stock trading, but these alternative currencies could have an ever larger effect.

The internet in 2022

It’s stunning to think that when HRH (RIP) had her coronation in 1953, canisters of monochrome film had to be taken to aeroplanes and flown to TV stations across the Commonwealth, so people could see the TV pictures.

Now, we can live-stream our jubilee parties (or non-parties!) in 4K colour to our friends on the other side of the planet!!

And that’s all happened within the Queen’s reign, the past seventy years.

The internet is amazing. And we haven’t seen the last of the changes. For example, the current hype for ‘Web 3.0’ and the metaverse.

Change is the norm on the internet.

Did I miss anything?

I’m sure I missed lots, but this article is getting rather long. Let me know if I’ve missed anything vital

What do you think was the most influential innovation for the internet in the last 70 years? Let us know below.

References

This post wouldn’t have been possible without these great resources (and Wikipedia!):

Add comment